New veterinary graduates need support and guidance during their first year in clinical practice, but few receive it—resulting in significant turnover. In fact, 30% of new veterinarians leave their first job within the first 12 months. This attrition is costly—not only to individual practices but to the greater veterinary industry. When new grads aren’t set up for success they experience diminished job satisfaction and may be at risk for leaving the field altogether.

Mentorship can end this harmful trend by giving young vets the coaching and skills they need to enjoy long, healthy, and rewarding careers. However, traditional mentorship programs often fail because they rely on the mentor—not the mentee—to be the sole driving force.

Why good mentors aren’t enough

Veterinarians and practice owners often comment that new graduates require too much hand-holding or babysitting. Despite coaching, new grad hires continue to struggle with skills such as decision-making, client communication, and exam room efficiency. This delayed growth often happens when too much responsibility is placed on the mentor, instead of the mentee, to create a sustainable and successful mentorship experience. Unfortunately, this accidental dependency can erode the mentor-mentee relationship altogether—leaving new grads to struggle on their own.

Successful mentorship is mentee-powered

Successful mentorship requires the mentee to take the driver’s seat. But, after years of didactic learning, many new veterinarians don’t realize that transitioning to clinical practice requires taking full ownership of their learning.

The Western College of Veterinary Medicine in Saskatchewan has led the charge on mentee development, and incorporates mentee skills into their curriculum to better prepare new veterinarians for a successful mentorship experience. The information in this article is adapted from the work of WCVM faculty (Drs. Hodgson, Freeman, and Darling) to prepare new vets to be active mentees.

Through self-directed learning, mentees can gain vital habits and skills such as self-motivation, problem-solving, and receiving and incorporating feedback. Together these abilities help new grads build consistent professional growth, develop confidence in their skills, and accelerate their independence in the clinical setting.

Setting the pace with self-directed learning

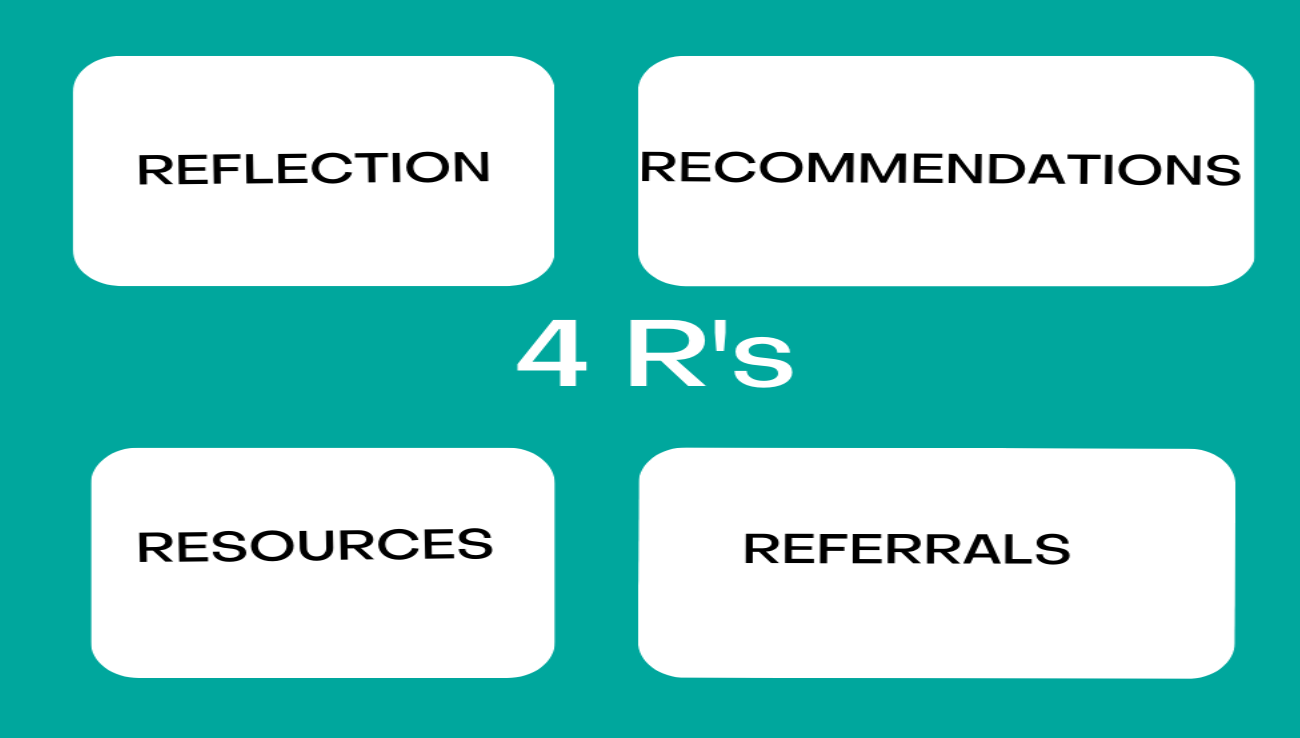

Self-directed learning is central to the mentee-mentor relationship, but it must be taught. Built on clear definitions and expectations for both the mentee and the mentor, the new veterinarian’s skills are constructed, rehearsed, and refined around a self-guided framework and action steps known as the 4 R’s of mentorship.

Step one—defining the mentor-mentee relationship

Like any effective learning experience, establishing clear definitions for mentorship can prevent confusion and set appropriate expectations.

By definition, mentoring is an intentional, consistent, collaborative process whereby experienced colleagues appropriately support mentee development. Unlike shadowing, mentorship is active, ongoing, and requires mutual participation and effort. It is also important to note that mentors are to support—not manage or design—mentee development.

The mentee must also define their needs and goals for the mentorship and use this criteria to identify and solicit suitable mentors. Once a mentor is acquired, the mentor and mentee work together to set mutual expectations such as:

- Communication frequency

- Mentee goals

- Where, when, and how often to meet

- How questions will be asked and addressed

Step two—The 4 R’s of mentorship

The 4 R’s provide a road map for the mentorship process. When the mentee encounters a challenging situation or case, they can work through the 4 R’s by asking open-ended questions to their mentor and receive direction or focused feedback.

The 4 R’s of mentorship include:

- Reflection — Reflection teaches the mentee to pause and intentionally think over the problem or case, reviewing any necessary data, conversations, or clinical findings. Instead of finding a solution, the mentee’s objective here is to look for sticking points. These could be gaps in their learning, errors, or a lack of preparation. Mentees review these sticking points with their mentor for focused discussion and guidance.

- Recommendation — Mentees can solicit specific input from their mentor. Depending on what is needed and the mentee’s learning stage and confidence level, this could be treatment recommendations, affirmation, or a fresh perspective.

- Resources — If additional information or skills are needed, the mentee can ask their mentor to direct them toward appropriate resources such as texts, journals, online forums, or learning opportunities. This R shapes the mentee’s information-gathering abilities and helps them learn how to find answers on their own.

- Referral — Mentees can ask for referral to experts or specialists who can provide insight into their case. This R helps cultivate critical thinking and builds the mentee’s resource network beyond the practice.

By continually revisiting the 4 R’s, mentees can rehearse taking ownership of their challenges without feeling overwhelmed or isolated. With a clear system in place, they learn how to seek constructive, targeted help without becoming dependent. Over time, the mentee’s acquired skills and knowledge are layered upon this framework. As this base forms, mentees experience increasing confidence, competency, and autonomy.

Next steps—self-directed learning in action

In Part 2 of this series, we’ll discuss how mentees and mentors can apply the 4 R’s in self-directed learning to identify and achieve specific learning goals and work through common first-year challenges.

If you’re looking for a simple way to provide consistent guidance and training for your new veterinary graduates, consider outsourcing your mentorship program to Ready, Vet, Go. Our six-month online platform is suitable for small and corporate practices and we also offer private coaching sessions for one-on-one support. Check out our programs, or contact our team to discuss your organization’s specific needs.