This article is a follow-up to Part 1 of this series, where we discussed the need for mentee-driven mentorship and outlined the first two components of self-directed learning.

Mentorship is a critical component of a successful experience for new veterinarians. However, many new vets fail to realize that much of the responsibility in a mentor-mentee relationship falls on them. Early-career veterinarians should take the wheel and direct their mentorship experience to receive the guidance they need to develop and flourish in their new careers.

Mentee skills recap

The mentee skills program and the 4 R’s of mentorship were originally designed and implemented by the Western College of Veterinary Medicine (WVCM) in an effort to improve the transition between veterinary school and clinical practice. The content outlined here is adapted from the original work by Dr. Hodgson, Freeman, and Darling.

If you missed part one of this series, you can find it here.

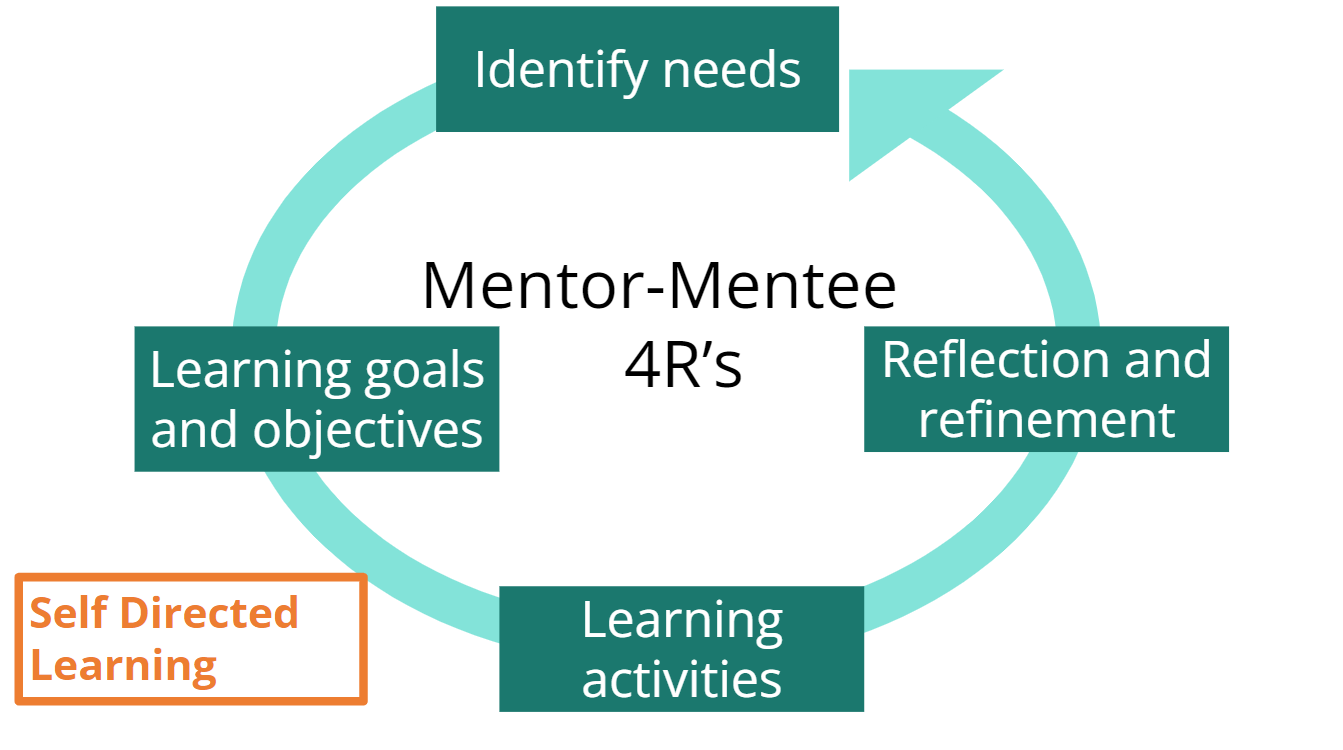

Now that you are all caught up, let’s jump back in where we left off, using the 4 R’s to guide self-directed learning.

Step three—the 4 R’s in action

This step focuses on applying the 4 R’s to structure and shape self-directed learning. Whenever the mentee faces a challenge in clinical practice, they can follow the steps below—working through the 4 R’s when appropriate—to initiate and build steady growth and address any learning or experience gaps.

#1: Identifying needs

Mentees should routinely evaluate their learning needs—including situations where they find themselves uncertain, lacking certain skills, or simply lacking confidence. These can include obvious areas like surgery or the physical examination or—as is often the case—soft skills such as navigating difficult conversations, collaborating with the team, or managing emotions.

For example, one common struggle among new grads is initiating quality-of-life conversations with clients. By naming this need, mentees and their mentors can work together to devise an actionable learning plan.

#2: Establishing learning goals and objectives

Once the need is identified, the mentee and mentor work together to devise appropriate learning goals to measure mentee progress. The act of recording these goals and objectives in a personal notebook can help mentees manage their learning and track successes.

Mentees should be as specific as possible when naming and planning their learning goals. Here’s a user-friendly template adapted from the Western College of Veterinary Medicine workbook:

“After active engagement in (learning activity determined in step 3), I want to be better able to (learning objective).”

Following our quality of life example, this entry would read:

“After active engagement in role playing activities with my mentor, I want to be better at initiating quality of life conversations.”

This simple goal-setting format is a valuable professional skill that mentees can use in all areas of their career to foster personal and professional growth and development.

#3: Performing learning activities

Next, the mentee and mentor work together to determine the best learning activities to help the mentee reach their goal. Depending on the mentee’s learning style and resource access, these activities may include:

- Role-playing

- Reading and research

- Live lab sessions

- One-on-one coaching

Mentees can choose a variety of activities to reach their learning objective but should start with one to prevent overwhelm and ensure concentrated effort. In our example, the mentee and mentor may decide to practice role-playing in a one-on-one setting where the mentee would feel safe.

#4: Reflect and refine

At regular intervals, the mentee and mentor should talk through each active learning objective and the mentee’s progress. If the goal has been achieved, the mentee can move on to another need and begin again at step one. If the goal is still unattained, the mentee-mentor team should evaluate whether the current learning activities are effective, whether measurable progress is being made, or if the objective and the method should be reconsidered and refined.

In our quality-of-life example, the mentee practices roleplaying with the mentor (i.e., a safe setting), and then applies the skill during a real appointment. Afterward, the mentee reflects on the attempt with their mentor, weighs the outcome (i.e., has an appropriate comfort level been achieved?), and determines if that learning objective has been satisfied.

Going forward—implementing mentee skills in practice

Mentee skills are certainly an area for further study and development for the veterinary field at large, and it will take time to determine what strategies are best for supporting new veterinarians and their mentors. Early takeaways from WCVM are positive, and the researchers report increased engagement among new grads who are trained in self-directed learning techniques.

For now, veterinary practices seeking to conduct their own mentorships can support new hires by clearly defining the mentorship process from the outset—including the expectations and responsibilities for each role—and adopting a learning system that empowers mentees to step up and own their mentorship experience.

If mentorship sounds like a great idea, but you don’t have the time or resources to dedicate to advising a new veterinarian—or a group of new associates—consider outsourcing your mentorship to Ready, Vet, Go. Our six-month veterinarian-led online program and private coaching opportunities can expedite the onboarding process, eliminate common roadblocks, and give your new veterinarians the confidence and skills to become productive and fulfilled team members.

Visit our membership page or contact us for details!